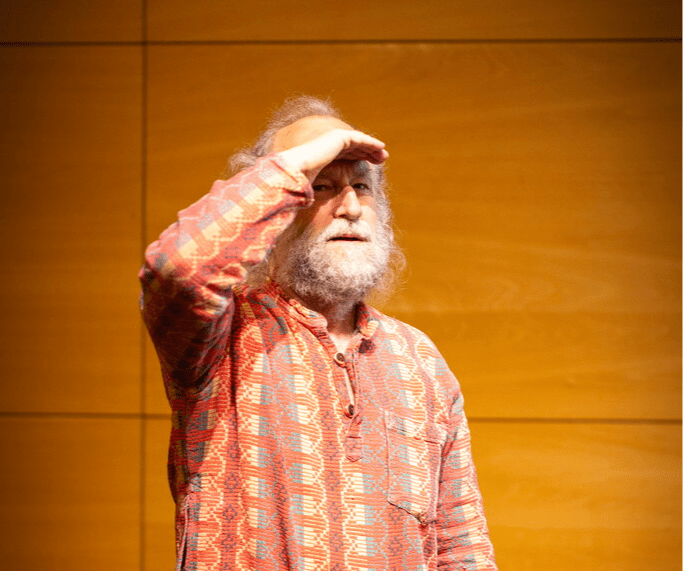

Marc Schoenauer agreed to take part in an interview-portrait.

Can you introduce yourself and tell us about your career path?

In a few lines -

I entered ENS-Ulm in 1975 after preparatory classes at Louis-Le-Grand, obtained a DEA in Numerical Analysis at Paris 6 in 1979, then a postgraduate thesis of the same calibre at CMAP-X in 1980, and was recruited as a CR CNRS researcher the same year. The advent of microcomputing and my introduction, thanks to Michèle Sebag, to machine learning and genetic algorithms made my career path a little chaotic, and I did not obtain my HDR (Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches, or accreditation to supervise research) until 1997. I was then recruited as a DR Inria in Rocquencourt in 2001, and founded the TAO team (Learning and Optimisation theme) with Michèle in 2003, within the embryonic Saclay centre. DR1 in 2008 then DR0 in 2023, DS (Scientific Delegate) of the Centre from 2010 to 2016, then ADS (Deputy Scientific Director) from 2019 to 2024, the day of my retirement and my transition to emeritus status. I was editor-in-chief of MIT-Press ECJ (2002-2009) and chair of ACM-SIGEVO (2015-2019). I also had the great honour of being part of the team led by Cédric Villani to draft the eponymous report on the national strategy for AI, published in March 2019 [link to the report "Giving meaning to AI, 11/2018].

In detail, and above all, giving credit where credit is due ;-)

My career path is simply the result of a series of encounters and strokes of luck, each more improbable than the last.

I will quickly gloss over the culturally and scientifically privileged social background I come from (my mother was a nurse and my father an engineer), which already set the course for my future. I was, of course, a very good student at school, but above all I was lucky to have teachers who knew how to guide and encourage me. I am thinking in particular of two teachers, true ‘hussars of the republic’, Mrs Nédellec in Year 4 in Brest, and Gaston Beltrame in Year 6 in Ollioules, as well as two maths teachers, Jean Trignan in Year 9 in Toulon, and Denis Gerl in Year 13 at Louis le Grand, the sixth form college where I had the incredible opportunity to enrol halfway through my final year thanks to Sacha Feinberg, who was a philosophy teacher there, whom I had met... on a skiing holiday a few years earlier. In addition to advanced mathematics, I learned humility there, joining a number of other students who were much more gifted than me (including two future Fields Medal winners, Jean-Christophe Yoccoz and Pierre-Louis Lions). But I was on track, which led me to a preparatory class there, then to the ENS Ulm.

After a (less than glorious) teaching qualification in mathematics and a postgraduate diploma in numerical analysis at PVI, I was contacted (I never knew why or how) about a thesis (at the time, a one-year postgraduate programme) by Jean-Claude Nédelec, director of the CMAP (Centre for Applied Mathematics) at the École Polytechnique, a laboratory that was booming at the time, in line with the national expansion of applied mathematics. This expansion was reflected that year in the opening of positions reserved for applied mathematics by the recruitment committee of the Maths section of the CNRS. Lack of informed candidates? Normalien profile? In any case, I joined the CNRS in 1981, even though I had not yet defended my thesis!

Then, at the same time as hepatitis (A!), I caught the personal computing bug. But at that time, research was carried out exclusively on mainframes, and the first PCs were seen at best as useful toys. For example, there were no computer science courses in my curriculum at the ENS except for a week-long introduction to Fortran when I arrived, which was kindly snubbed by the ‘pure’ mathematicians we thought we were.

But PCs were quickly followed by workstations, and everything I had learned on the job at home became invaluable knowledge for their deployment in the lab, in the absence of engineers trained in the subject (or any engineers at all, for that matter). Hand in hand with my accomplice Joël Frelat, a mechanic and friend, we installed (and maintained!) a network shared by the CMAP and the LMS (Laboratory of Solid Mechanics), then provided practical training in scientific computing, also shared by the two departments.

But what about research, you might ask? Because although the CNRS left me alone, given my IT activities, my lack of scientific publications was starting to become a problem.

On a personal note: during my years at ENS, I met Michèle Sebag, who became my partner after graduating from ENS (and still is today, but that's another story). Together, we had two daughters (fantastic, as our American colleagues would say, but for once I agree – knowing that I risk being accused of bias) ... and wrote a few articles (more than fifty :-)

But let's get back to the matter at hand. Michèle, while working at Thomson CSF (now Thalès) after graduating from ENS, became interested in Artificial Intelligence, particularly through Jean-Louis Laurière's courses at Paris 6. After leaving Thalès, she defended her thesis on learning in 1990, funded by the LMS thanks to the visionary spirit of Joseph Zarka, who was also responsible for her recruitment as a CR1 CNRS researcher in the Mechanics section! This is how Michèle and I were able to start working together in an informal team at the École Polytechnique on AI applied to numerical simulation, an issue common to both labs. This led me to encounter genetic algorithms at the ICML conference in Austin in 1990, and that was the beginning of my career in the field of evolutionary algorithms, which was still in its infancy at the time. I quickly began working on the application of these algorithms to scientific computing problems (mainly shape optimisation), and, one thing leading to another, I started proposing algorithmic innovations and publishing in the leading conferences in the field (first ICGA article in 1993). I also found myself at the forefront of bringing together French teams that were beginning to work on the subject, thanks in particular to Evelyne Lutton from Inria... and it was in her team that I applied in 2001 for the position of Director of Research, following a chance encounter with Gilles Kahn. I also had the opportunity to attend the first PPSN conferences, a series of European conferences on the subject, and to participate in the European network of excellence Evonet (as its name suggests), and to begin my international ‘political’ career, which led me to be elected Chair of the ACM Special Interest Group on Evolutionary Algorithms (SIGEVO). On this subject, I would like to say that I owe a great deal to CMAP and its director, who funded missions for conferences where I didn't even have a paper, or for Evonet preparatory meetings before it received funding (my first personal contracts date from 1997-98). This allowed me to enter the Inria DR competition with already well-established international visibility, which, in addition to the low pressure due to the fact that this competition was known to be only an internal promotion competition until then, allowed me to achieve the Holy Grail.

It so happened that we were at the beginning of Inria's golden age, which saw it double in size in 10 years, with the creation in 2002 of the new ‘Futurs’ centre, a breeding ground for the Saclay, Lille and Bordeaux centres. At the same time, Michèle had moved from the mechanics section at the CNRS to the IT section, becoming a senior researcher at the IT Research Laboratory at Paris-Sud University. What a coincidence! The Inria Futurs centre, which became the Saclay Centre in 2008, was specifically looking to create joint teams with Paris-Sud University in Saclay, and this marked the beginning, in 2003, of the TAO (Learning and Optimisation) adventure, co-directed by Michèle and myself (we were keen on this, even though Inria only wanted one person in charge) . And Futurs had the means to achieve its ambitions, which enabled us to immediately recruit Olivier Teytaud (2004).

Scientifically speaking, the combination of learning and optimisation, which is now commonplace thanks in part to the explosion of deep neural networks, was completely original at the time. It has led to a number of highly visible successes, such as, on the learning side, the MoGo Go game programme, a precursor to DeepMind's AlphaX programmes a little later, and on the optimisation side, the maturation of the CMA-ES algorithm, thanks to the recruitment of Anne Auger (CR, 2006) and Niko Hansen (CR1, 2009), who then went on to strike out on their own in 2016.

As we can see, TAO has benefited greatly from the growth of the Futurs/Saclay centre, recruiting five Inria researchers in 10 years, but also, due to its affiliation with Paris-Sud University, from two associate professors (Philippe Caillou and, more recently, François Landes) and three professors (Cécile Germain, on internal mobility from LRI, Isabelle Guyon and, more recently, Sylvain Chevallier). To these must be added (attractiveness or snowball effect?) the arrivals on mobility from Yann Ollivier (CR CNRS) and Guillaume Charpiat (CR INRIA). However, such growth also inevitably leads to a dispersion of research topics, further encouraged by the incredible rise of AI. With the departures of Anne and Niko, as well as Olivier, Yann and Isabelle to deep tech, the optimisation component of the team has gradually declined, focusing for a time on AutoML (algorithm selection and configuration) before virtually disappearing today. This is all the more so as several recruitments, led by Cyril Furtlehner, have enabled the group's statistical physics component to reach critical mass: although the links between learning and statistical physics are now obvious, this was far from being the case when he was recruited as a CR1 in 2007.

In addition, I was becoming increasingly involved in research management tasks (see next question), leaving me with less and less time for my own research. But emeritus status now allows me to return to work, since I can no longer exercise any responsibility on behalf of Inria. This has given me more time for myself, although I also intend to enjoy more time away from research (what we call ‘free’ time before retirement :-)

As a (provisional) conclusion, Michèle and I feel that we are leaving Guillaume and Cyril with a team that is still active and productive, and to whose activities we intend to continue contributing: in addition to the links between AI and statistical physics already mentioned, the team's current research topics are focused on what is known as ‘good AI’ : explainability and causality, frugality, bias detection and correction. To these topics must be added a major component on ‘AI and numerical simulations’, which brings me back to my initial concerns at the start of my career: precision, reliability and speed of simulations, whether based on traditional scientific computing, data mining and generative AI, or hybrid approaches. We have come full circle.

How did you manage to balance your research activities with your research management duties (as Deputy Scientific Officer)?

To sum up: everyone has to do their share of the washing up, but it shouldn't always be the same people who do it (and I'm not just speaking for myself here; I could name several other colleagues). But my boy scout side means that I've rarely been able to say ‘no’ :-(

On a more personal note, to be honest, I didn't really succeed. Before becoming ADS, I had already been DS (scientific delegate) at Saclay for six years, then I was co-opted by Cédric Villani to write that famous report. And all these responsibilities are extremely time-consuming. Especially since they snowball: my participation in the Villani report made me extremely visible in the field of AI, both in France and in Europe. I was therefore asked to represent Inria at various meetings, both at national and European level. I thus became PI for Inria for several networks of excellence (TAILOR, 2020-2024, and VISION, 2021-2024), then coordinator of the large European network AI, Data and Robotics Environment (2022-2025). It was undoubtedly to formalise these various roles that the position of ADS IA was created for me in 2020, with a poorly defined scope (everyone is involved in AI these days!). And to top it all off, at the end of 2021, I agreed to be one of the three ‘sherpas’ of the PEPR-IA.

But to get back to the question, all these time-consuming activities effectively took me away from research. The worst part was not having enough time to simply keep up with the bibliography in my field, knowing that I also had to stay tuned to the more ‘political’ news about AI. So I did my bibliography through my PhD students. Fortunately, I had some very good PhD students, but it was still unsatisfactory.

What do you remember most about your involvement in writing the "Villani report"?

- Cédric Villani's extraordinary personality, his prodigious memory, his exceptional ability to synthesise information, and his humanity.

- The enrichment provided by the different points of view within a largely multidisciplinary team, including members of the National Digital Council from diverse backgrounds, united in a common cause. As an anecdote, while Cédric Villani was a Macronist MP (he later became a Green before leaving politics), the team was undoubtedly left-leaning :-)

- The incredible heterogeneity of the reactions of official institutions to the arrival of AI: from the quasi-militant motivation of the Secretary of State for Ecology, a close-knit team determined to make the most of it for their ‘cause’, to the flawless preparation of the gendarmerie, which had already considered the misuse of AI and how to try to prevent it, and, unfortunately, the shameless cynicism of the Ministry of Economics and Finance (we only saw one member of the minister's cabinet), solely concerned with the possible repercussions in the form of social unrest (i.e., it doesn't matter if the profession of lorry driver disappears as long as it is gradual and therefore does not lead to large-scale social unrest). The same heterogeneity can be found among the trade unions (no names mentioned :-)).

- The difficulty in predicting the side effects and/or misuse of recommended measures - even if this seems obvious in hindsight. For example, authorising researchers to work part-time for a private technology company was fraught with untenable constraints...

Do you remember your impressions during your first few months at Inria? When was that again?

It was in 2001. I was extremely lucky to be recruited directly at DR2 level.

My first impressions were: ‘But it's just like the CNRS!’ :-)

Let me explain: at the CNRS, there was a certain snobbery that considered Inria to be good, but not as good as the CNRS. In particular, because you couldn't really do what you wanted, you absolutely had to have industrial contracts. In short, not only was this fake news, but I quickly discovered that it was actually the exact opposite: I had signed my first contracts (European or industrial) as a CR CNRS at CMAP, and I had to do all the administrative paperwork myself. So when I discovered Inria's services, I was delighted! And that hasn't really changed since, despite the institute's change in size. At the CNRS, on the other hand, things have changed a lot, and for the better: it seems that they now also have support services worthy of the name (did they copy us? :-)

The other striking fact was that Inria was not just a concept, but actually existed. This was undoubtedly due in large part to the very small number of ‘hierarchical’ levels between the basic researcher and the top of the pyramid: the REP (team leader), the DCR (centre director), and then Gilles Kahn himself. In particular, Gilles is known for having been the last person to know all the Inria researchers by their first names and their research topics, which he could discuss if you ran into him in the canteen or elsewhere. Another example: a few weeks after I joined Rocquencourt, I was invited to meet Bernard Larrouturou and Gilles Kahn, who insisted on having this interview with all new arrivals. In contrast, I never saw a single CNRS official in 20 years at CMAP-CNRS, to whom I remain very grateful for paying my salary and giving me complete freedom, but who remained a totally abstract entity. And I would like to believe that the increase in the size of our institute has not too greatly changed this state of affairs...

Looking back, what memorable event or moment from your time at Inria, or what anecdote can you share with us?

I have already mentioned Gilles Kahn, and I still get emotional when I think of his last New Year's message in January 2006, in which he emphasised the importance of planting trees that we know we will not see grow. ..

You have already drawn some conclusions about developments in your field of research in recent years (see link here). What advice would you give to young colleagues who are now getting involved in AI as part of an Inria project team?

Don't try to cover the entire field, although you should keep abreast of the main advances (there are some very good tools for this), but don't hesitate to delve deeply into one or two very specific topics, and above all, don't be afraid to take the road less travelled, however crazy it may seem at first glance, while recognising that you may have taken a wrong turn.

What values do you share with Inria?

Academic freedom, which is essential to the advancement of science and ideas, particularly blue sky research; and open science, which should not even be up for debate.

At the organisational level, financially (quasi-)autonomous project teams, implementation of the “small is beautiful” precept, even if the latter unfortunately seems outdated today.

What advice would you give to the youngest members of our Inria+alumni community – both in terms of age and seniority – to boost their career prospects?

I'll start with an anecdote from British psychologist Richard Wiseman (The Luck Factor). He placed two classified ads asking for volunteers for psychology experiments. One sought people who thought they were generally lucky in life, the other sought people who thought they were unlucky. He asked them to go to a given address on a given day to answer various questions. But in fact, the experiment took place before they even rang the doorbell: a £5 note was placed on the ground a few metres from the door, not in plain sight, but still visible. The proportion of people who saw and picked up the note was significantly higher among those who considered themselves lucky than among those who considered themselves unlucky. Luck is a state of mind, Wiseman concludes.

And that will be my conclusion here too: be open to opportunities, and luck will smile on you, and it won't just be luck.

What popular wisdom has known for a long time: fortune favours the bold, as our ancestors used to say.

What could you offer them?

I strongly believe in learning by example: be open to opportunities, but also learn to say no. And I realise that I'm contradicting myself, since I didn't really know how to say no when I should have :-)

To conclude, a word or quote to sum up this portrait?

Luck is a state of mind: be ready!

© Inria / Photo C. Morel

Comments0

Please log in to see or add a comment

Suggested Articles